Food insecurity is defined by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) as “a household-level economic and social condition of limited or uncertain access to adequate food.” Generally, this indicator refers to households who don’t have enough food, particularly healthy food, to eat due to a lack of money and other resources. There are slight variations in how different organizations define food insecurity, but all relate to households who lack healthy food.

How big is the problem?

During the COVID-19 pandemic, a spotlight was focused on food insecurity as many individuals lost their jobs, schools closed resulting in children not getting meals there and other normal sources of food were curtailed, resulting in households being unable to obtain all of the food that they needed. The U.S. Census Pulse Survey results indicate that those who sometimes or often did not have enough to eat due to lack of resources increased from about 20% pre-pandemic to 28% by mid-2021.

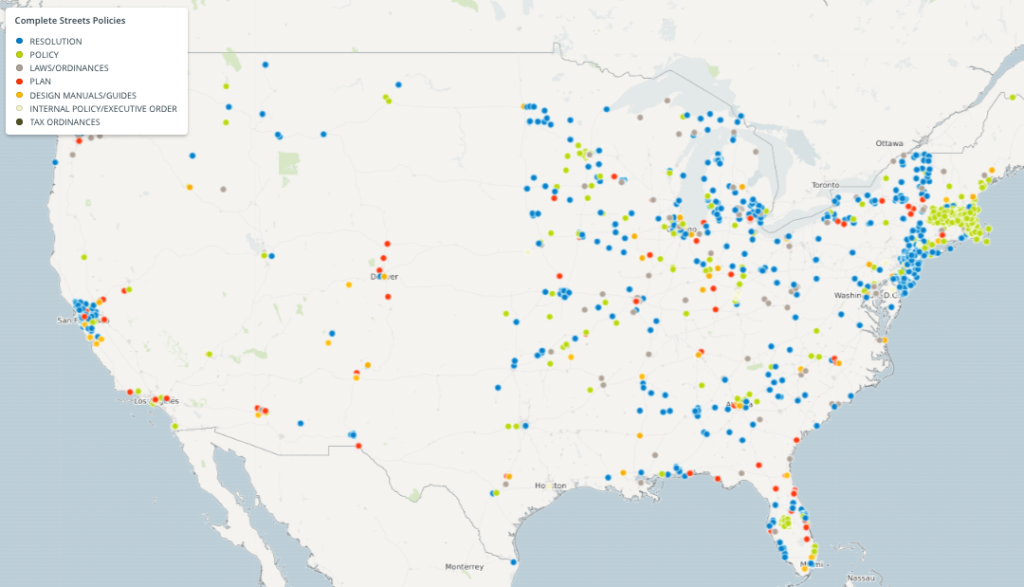

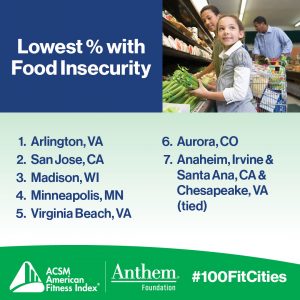

The Feeding America non-profit group produces annual “Map the Meal Gap” reports that include estimates of food insecurity at the city level. Their most recent report (2020) was used as the measure of food insecurity in the 2021 American Fitness Index (Fitness Index). Feeding America uses U.S. Census Current Population Survey data to measure of food insecurity based on a well-established statistical model using unemployment rates, median incomes, racial demographics and other factors shown to be determinants of food insecurity. Across the 100 cities included in the 2021 Fitness Index, there was almost a three-fold difference in the percentage of households with food insecurity, from a low of 6.7% for Arlington, VA, to a high of 18.2% for St. Louis, MO.

What is the impact of food insecurity?

A considerable amount of research has examined the physical and mental impact of food insecurity, including poor physical health outcomes, inadequate intake of key nutrients for optimum functioning and increased risk of chronic disease. Associations also exist between food insecurity and obesity along with poor glycemic control among those with diabetes. Of particular concern from a fitness perspective is that food insecure households may not consume an adequate amount of protein, a nutrient essential for a variety of bodily functions, including building and repairing muscles, bone health and development and stabilizing blood sugar.

Healthy cognitive, psychological and emotional development among children is also dependent on them consuming sufficient amounts of nutritious food. America’s poor and near-poor children are at higher risk of lower academic achievement and behavioral problems. Food insecurity has been associated with poor psychological and cognitive functioning, higher probability of behavioral problems and higher levels of aggression and anxiety among children. Food insecure women are more likely to experience prenatal depressive symptoms than food secure women. Another consequence of food insecurity is poor sleep which can cloud thinking and lower energy, as well as decrease the ability to make good decisions. The profound impact of food insecurity on individuals’ physical and mental health made a clear case for adding this indicator to the Fitness Index.

How is food insecurity addressed at a policy level?

The federal government recently expanded the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Women, Infants and Children (WIC) and other safety net programs that support low-income children and mothers during the pandemic to help increase access to food among those in need. These programs provide more than half of all food support for households in need. The USDA has also funded innovative demonstration projects such as creating and distributing meal boxes that contain a week’s worth of groceries that can be delivered to those in need.

What can city officials do to reduce food insecurity locally?

In addition to supporting existing food banks, pantries and other food providing programs, many city officials have supported the development and maintenance of innovative and effective programs to improve access to healthy food. The following examples offer city officials, local businesses and residents an opportunity to get involved in reducing food insecurity in their communities.

- Organize food providing programs into a network that shares information and resources as well as analyzes food need patterns to build capacity in advance of expected needs.

- Develop apps or websites to make local food resource information readily available. Information about food access is a critical resource particularly for households newly in need.

- Establish mobile food pantries and farm produce trucks to carry needed food into the food deserts and to others in need of food.

- Partner with farm-to-table and farm-to-school programs which are effective ways to ensure those in need have access to fresh produce while at the same time supporting local farmers.

- Start community gardens, using city property when allowed, as public gardening spaces. Those interested are assigned an area in a shared garden where they can grow fresh fruits and vegetables. Seeds, water, tools and other resources are often provided or shared when available.

- Create a food rescue program that gathers unused food from restaurants and similar food preparation organizations that might have otherwise been discarded, and distribute these food items to agencies that provide hot meals to those in need. Alternatively, food rescue programs can work with local farmers to glean what is left in farmers’ fields after their harvest. This rescues fresh fruits and vegetables that would otherwise go to waste in fields.

- Support organizations that help those in need understand their eligibility for benefits and help them navigate the application process. State agencies are responsible for distributing SNAP and WIC benefits, but many eligible people are not enrolled because applying for these benefits can be cumbersome and confusing.

While the problem is large, there is much we can all do to reduce food insecurity across the country. Clearly, having access to healthy food is important in all cities, and innovative, effective programs can be used by city officials to improve the access.

If you or someone you know is experiencing food insecurity, you can find help at www.feedingamerica.org/need-help-find-food.

Author: Terrell W. Zollinger, DrPH, Professor Emeritus, Indiana University

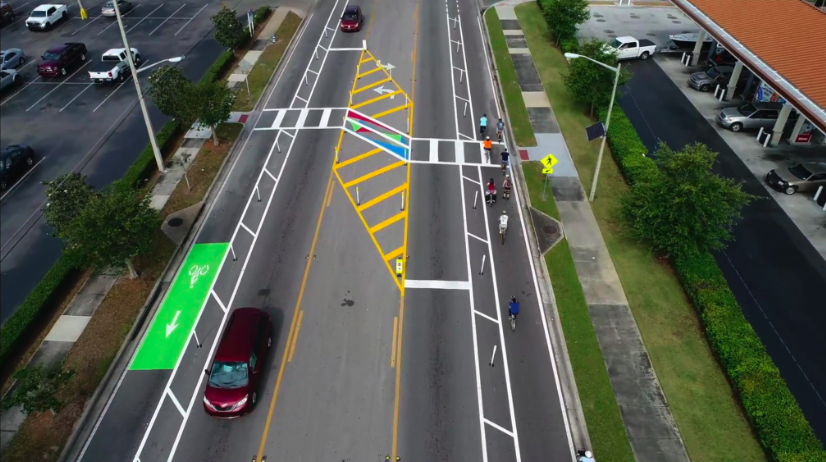

#5 What do Complete Streets look like?

#5 What do Complete Streets look like?